In Loving Memory of My Brother Pini

Eich naflu giborim. How the mighty have fallen. These are the words Pini said to me late one night from his hospital bed. They sound like bitter words, but that was his sense of humor coming through at 2 AM, amidst the cacophony of machines, tubes, and night nurses. Those who did not know Pini well were unaware of his distinctive wittiness, which was often sarcastic and poignant. But I knew him, and so I laughed, sitting on that chair next to his bed all night long.

Pini was never left alone once he entered the hospital, a few days before Pesach. One or two of us were always with him, day and night, until he was moved to the ICU, where they did not allow night visits. Sometimes he was in a state of confusion because of the illness and the medications. And sometimes he was all there. But always, no matter what, he was exceedingly polite. Despite the pain and discomfort, he always responded with impeccable manners whenever one of us, or the amazing hospital staff, asked him a question. It was always “Yes, please,” or “No, please,” or “Excuse me.”

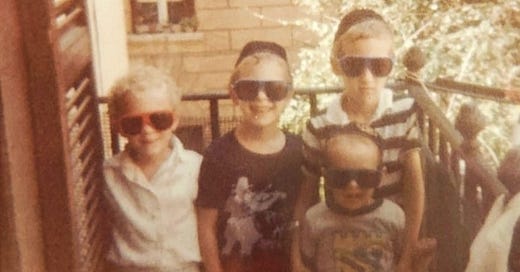

Growing up as we did, in the bubble of our Roman apartment, we were taught to be polite and respectful and always avoid a chillul Hashem. Which is not to say we were robotic children with fake smiles plastered on our faces. On the contrary, we were a rambunctious bunch, devising various ways to entertain ourselves and driving our parents up a wall day after day. But we knew that we were to behave as much as possible in public, and exemplify appropriate behavior. On our long train rides to Milan, a quick but piercing glance from our older sister was enough to set us straight. My aunt in Israel once joked that I had “European manners” because even as a child, I found it natural to use a knife with my meals. But I think it was the Hazan manners that our parents instilled in us.

Pini was not much of a troublemaker, and his politeness and respect for others were a natural part of him, which is why they came through during his hospital stay.

He had some health issues as a child, which did not make a difference to us, the gang of siblings who collected pine nuts in the parks of Rome or built a Lego tower to the ceiling. Pini was right after me in the order of siblings, but I was closer to the brother directly ahead of me in the seder hishtalshelus. Still, we spent a lot of time together, and I fondly remember the hours we spent recording “radio shows” on an empty cassette tape. Once, we recorded a segment with me as the interviewer and Pini posing as a scientist named Professor Picasso Intelligentini. We discussed whether children should be allowed to own toy guns (our mother was against them), a topic we analyzed in detail. That tape is lost to time, but the memories remain crystal clear.

Professor Squarcina, the doctor who was almost a member of our family, had a soft spot for Pini and referred to him as “Pinì” with the accent on the i. Pini had a beautiful voice, but he only sang in the privacy of our home. He loved Avraham Fried’s music as a child, and when my sister organized an Avraham Fried concert in Rome in the mid-90s, Pini must have been in 7th heaven.

Pini was a keen observer of the world and was not afraid to go against the grain when it came to his political opinions, holding leaders accountable and seeing beyond their grandstanding. Unlike so many, he made no excuses when a politician he supported did something wrong. I will greatly miss his voice in the political discussions on the family WhatsApp chat. In addition to following Israeli, American, and Italian politics, Pini was always up to date on the intricacies and intrigue of the Roman Jewish community.

When the police questioned us and briefly detained us once, when we traveled to Milan for school, Pini was one of the siblings for whom I was responsible, although I was all of 13 at the time. I remember him crying silently in the police station as we waited to find out what was going on.

Pini was named after our maternal great-grandfather, Elkanah Pinchas Gitman, known as “Kunye.” He was a Skverer chassid whose own father, Yehoshua, was close to the Skverer Rebbe. A Skver chassid who wrote about Kunye included the following story in his notes:

Reb Kunye recounted:

'On the night before my bris, my late mother had a dream. In the dream, she was standing by a river, drawing water from it, and filled her jug. After she had filled her jug, her father approached her and said, “My daughter, if you’ve already filled one, you can go ahead and fill another cup as well...” And that was the end of the dream.

In the morning, my mother told my father about the dream, and my father then told Reb Dovid of Tolna before the bris. The holy Tolner Rebbe said: “The meaning is this: You had planned to name the child 'Elkanah' after your father. So, your father-in-law appeared to his daughter in a dream to request that the child also be named after him.” And so, I was named ‘Elkanah Pinchas.’

Pini succumbed to an illness he battled with great courage and resilience, as we all stood by his side. נסתרות דרכי ה׳.

Losing a loved one feels exactly as you’ve heard or read. There is no escaping the cliches, but they are our current reality. You could be going about your day, working or taking a walk, or helping your child, when something will remind you of them, and it will hit you all over again that they are gone, and it’s not right, fair, or natural.

I will leave you with a story that you may have heard, but it bears repeating. During the shiva, a coworker of his told us that when Pini wanted to check the news while at work, he would clock out of the system so as not to “steal” work minutes and clock back in when he was done. Who does that? Only Pini.