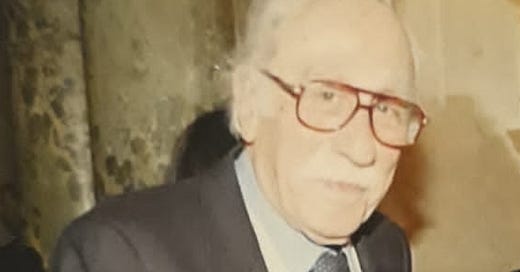

One of the בני בית in our home/Chabad Rome HQ was Professor Squarcina. A dear friend, he always came to the rescue when any medical issue arose. He was a unique character.

Professor Squarcina, or simply Squarcina, as we still refer to him—and trust me when I tell you he often comes up in our conversations—was a urologist, obstetrician, and gynecologist by profession, a distinguished doctor with a bushy mustache stained from years of pipe smoking. He practiced at a posh private clinic in the elegant Parioli neighborhood, the Quisisana.

As detailed in a previous post, waves of immigrants passed through Italy from the late 1970s and into the 90s. My parents brought the B. family to live in Ladispoli as shluchim for a few years and assist the Jewish immigrants from Russia. They knew Professor Squarcina and introduced him to my father when he was arranging brissin for Jewish Immigrants from the Soviet Union (and then the FSU) who had not been able to get circumcised as infants.

(This version of events is disputed. Mrs. B. says my mother introduced Squarcina to her, not vice versa).

Rav Hezkia z”l, a Lubavitch mohel, would come down from Milan to conduct the brissin. A Dr. was needed as well due to the age of the participants. Squarcina then got further involved with Chabad and by extension Judaism in general, which he had already been interested in.

Until his own Russian accent waned a bit, my father called him Sqvarcina. In turn, Squarcina called him Rav Kazan, which some Jews do as well if they are not used to the ח sound.

Squarcina was not Jewish, he had a Catholic background, but once the connection was made he never let go. His family originated from the South of Italy and some speculated that he may have descended from Crypto-Jews, but that’s pure conjecture.

His thirst for knowledge about Judaism was unquenchable. After learning the basics, he became a regular presence at shiurim and all community events (by which I mean the official Jewish community and Chabad). Everyone knew the good doctor and I think it’s fair to say he was more learned than many.

He was a fixture at Progetto Talmud, a series of lessons organized by Chabad with Italian rabbis from the Jewish communities, where he listened intently with his fingers over his mouth, nodding along. My sister also remembers him asking pertinent questions after my father gave talks in our home.

He sometimes asked my father to write to the Rebbe when something came up and he received answers that were relayed through my father.

He knew everything there was to know, and yet, he never converted. Some say it’s because he didn’t want to give up driving on shabbos—particularly after moving out of the city in retirement when he still wouldn’t miss the seder in our home.

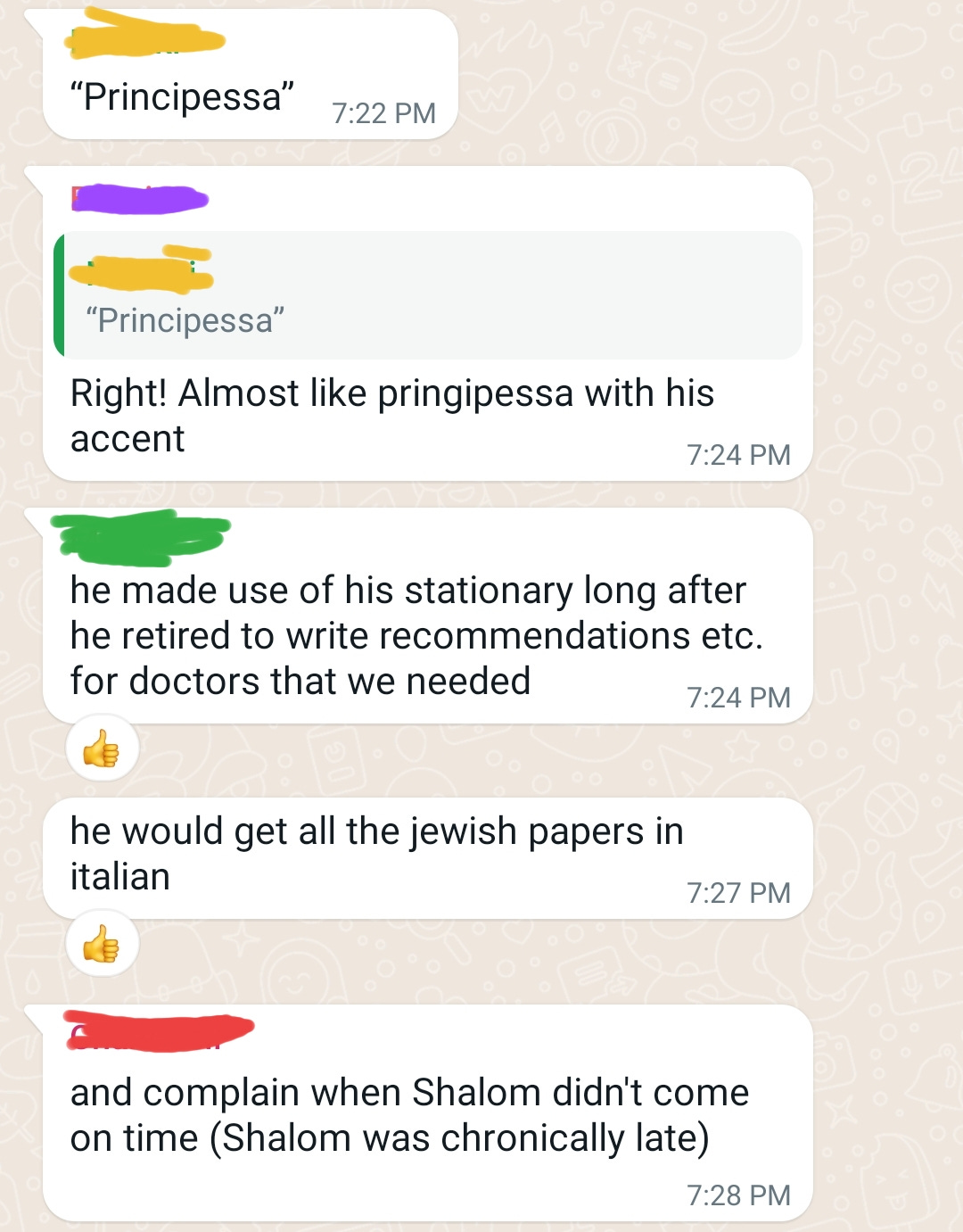

Squarcina was a permanent presence in our home and it really is not the same without him. He always sent flowers or other gifts with a card written in his unintelligible scrawl. He knew us all very well, as well as the others who frequented our home. He referred to my younger sisters as “principessa”, which in his strong Roman accent almost sounded like pringipessa.

He grew close to the B. family, the shluchim who lived in Ladispoli for a few years, and stayed in touch with them when they left.

He learned Hebrew with Eran, an Israeli medical student who always came to us for Shabbos meals, and frequently advised and helped him get into the programs he needed. He followed his career as he started a family in Israel (with another Israeli student and fellow El Al worker he met in our dining room) staying in touch as he built a distinguished medical career.

He was the one to call in an emergency because he was well-known in the medical community. He also volunteered to help ease a burden whenever possible, such as when my brother desperately needed formula, which was very expensive, and he secured boxes of samples which I can still picture very clearly in the ripostiglio, the pantry/utility room.

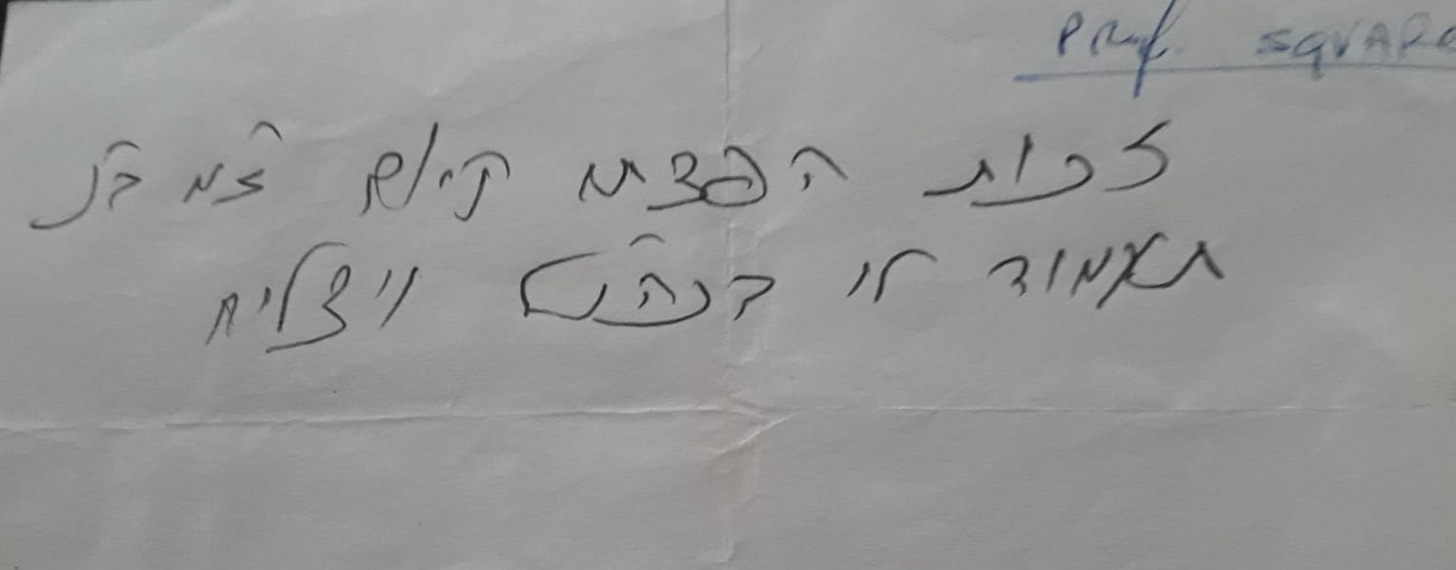

Long after he’d retired, Squarcina still used his official stationery to write referrals for doctors we needed.

My brother reminded me that he sometimes drove some of us home from shul after Yom Kippur, and stayed for the meal (which usually included a birthday cake for the brother who was lucky enough to be born on Yom Kippur).

He subscribed to all existing Jewish publications in Italian and brought his own Haggadah to our sedarim in his ever-present black leather bag. My sister remembers him frequently complaining that Shalom, the paper published by the Jewish community of Rome, was late to show up in his mailbox.

Squarcina always used the citofono, or door buzzer, even on Yom Tov, and one of us would run downstairs to open for him. This was completely fine of course, but it stood out because the other guests called out to us instead.

Before a complicated operation, the professor asked the Rebbe for a bracha. Rabbi Binyomin Klein from the Rebbe’s office called my father and relayed the following response:

____________ _____________ _____________ _____________ _____________ ______

With thanks to my family for the usual fact checking and for reminding me of anecdotes long forgotten:

Was he a single man? I never to question his sincerity. But a man seeks a sense of belonging to a community. Belonging to a family.

you can delete this comment but I believe it is brissim not brissin